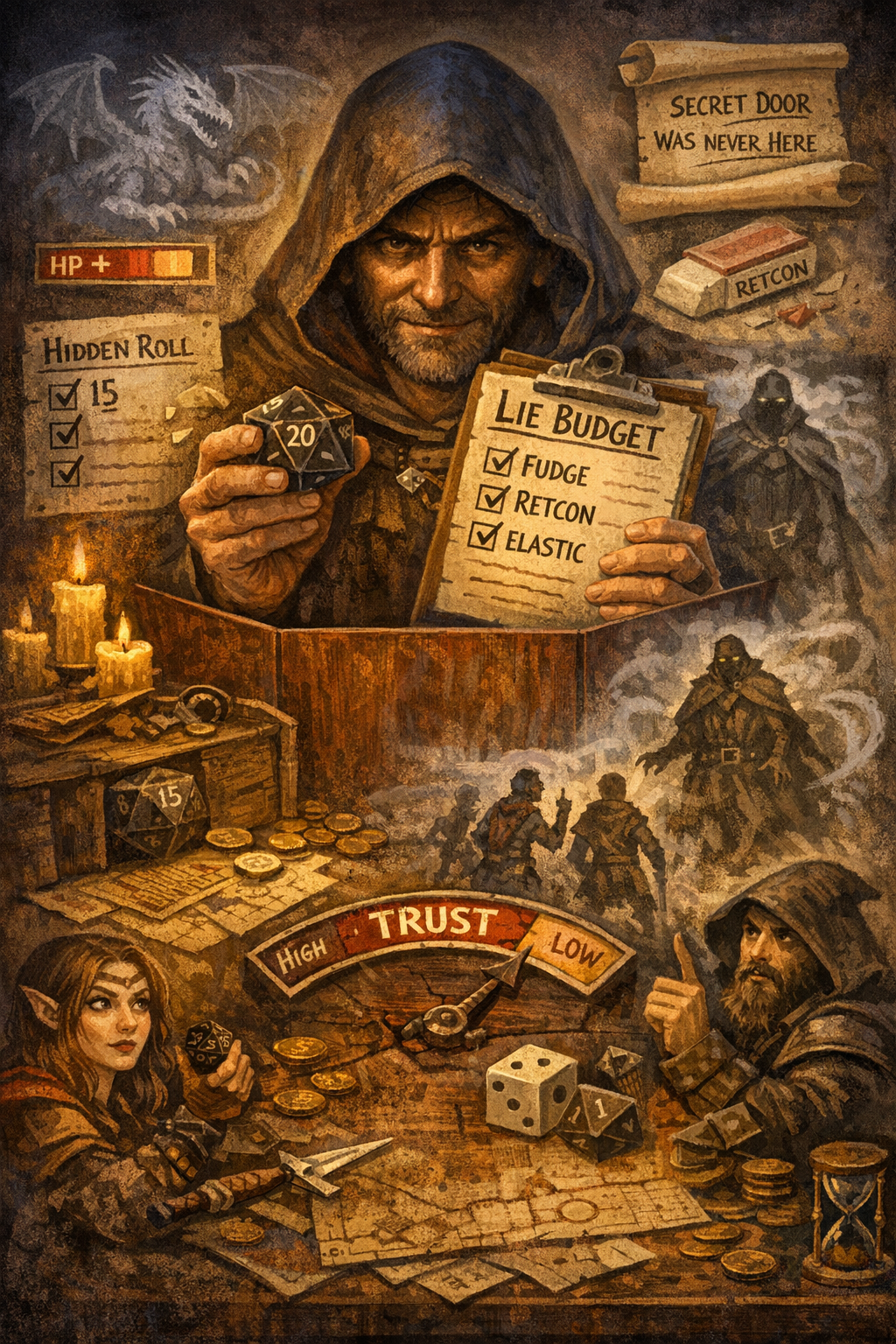

The “False Map” Technique: Using Unreliable Maps and Counterfeit Charts

When Right is Left and Left is...Left.

Dear Readers,

Maps feel like truth. You spread one on the table and suddenly the world becomes crisp: mountains are where the ink says they are, rivers behave, roads stay politely in place, and an X means the DM has promised you a reward for walking toward it.

That assumption is exactly why unreliable maps are such a powerful tool.

A “false map” is any chart the characters can acquire that is wrong in a meaningful way—outdated, biased, incomplete, propaganda, forged, symbolic, or outright malicious. Done well, it doesn’t punish players for trusting you. It turns travel into investigation, exploration into suspense, and geography into story. Instead of asking, “Which hex do we go to?”, the party starts asking, “Who made this? Why should we believe it? What’s missing?”

That’s the good stuff.

This post is a practical guide to using unreliable maps and counterfeit charts in a D&D game (or any fantasy TTRPG) without turning your campaign into a sad trombone of wasted sessions. You’ll get principles, flavors of false maps, prep templates, encounter frames, and a few ready-to-run examples you can steal shamelessly.

The golden rule: wrong maps must still be useful

Players don’t mind being misled by the world. They do mind being stalled by the GM.

So here’s the prime directive of the False Map Technique:

Even when a map is wrong, it should move the story forward.

If the party follows a bad chart into the wrong canyon, that canyon should still deliver something:

- a clue that clarifies the deception,

- a threat that raises the stakes,

- a relationship that changes the situation,

- or a choice that matters.

A false map is not a prank. It’s an engine for discovery.

Why this works (and why it feels fair)

A map is an in-world object. It is made by someone, for some purpose, at some time, with some knowledge and bias. Treating maps as artifacts—rather than authorial truth—adds a layer of realism and drama without requiring you to rewrite your setting.

And it’s fair because the game already teaches players to evaluate information:

- NPCs lie.

- rumors are messy.

- villains plant evidence.

- factions spin narratives.

Maps should be part of that ecosystem. They are just rumors with ink.

Types of unreliable maps (pick the flavor that matches your campaign)

Not all false maps taste the same. Choose intentionally.

1) The outdated survey

The cartographer was honest, but time wasn’t.

Maybe an earthquake rerouted a river. A war burned a bridge. A forest advanced. A dam turned a valley into a lake. A wizard’s tower fell and became a crater full of very impolite frogs.

Outdated maps are best when the world is dynamic: trade routes shift, borders move, disasters happen, and the party feels like they’re walking through a living history.

Payoff: discovery of change, plus consequences of “the old way” no longer working.

2) The propaganda atlas

Empires love maps because maps make claims.

Propaganda maps exaggerate borders, rename cities, erase minority settlements, omit enemy roads, and label whole regions “uninhabitable” to discourage migration. They’re political documents pretending to be geography.

Payoff: the map becomes evidence. If the party can prove a lie, they can embarrass a regime, expose a conspiracy, or rally allies.

3) The counterfeit chart

This is the con artist’s special.

A counterfeit map might be forged to:

- sell “treasure locations” to desperate adventurers,

- divert rivals away from a real find,

- funnel travelers into a bandit ambush,

- hide smuggling routes,

- or create plausible deniability for an employer.

Counterfeit maps shine when you want intrigue without needing a ballroom scene. The lie is in the paperwork.

Payoff: a face behind the fraud, and the chance to flip the con back onto the con artists.

4) The trap route

Somebody wants the party to go somewhere specific.

Maybe the “safe pass” is a dead end with a rockslide waiting. Maybe the “shortcut” goes through a cursed battlefield. Maybe the “ruins” are actually a cult checkpoint.

This flavor is sharper and more dangerous, so be careful: it works best when the party can detect the trap through play—tells, inconsistencies, local warnings, survival checks, or suspicious details on the page.

Payoff: tension and victory through caution, plus a new antagonist who planned the route.

5) The symbolic pilgrimage map

Not every map is meant for engineers.

Pilgrimage maps often depict routes by meaning rather than scale: “Three days to the shrine” might mean “three hardships,” not 72 miles. Landmarks might be spiritual milestones. Rivers might be drawn as serpents because that’s how the culture understands them.

This is excellent for mythic fantasy, fey journeys, and “the land responds to story” campaigns—provided you give players discoverable rules, not pure randomness.

Payoff: the party learns that interpretation is navigation, and that belief can shape the path.

6) The reality-warped chart

Sometimes the map is wrong because reality is wrong.

A moving forest. A wandering island. A dungeon that reconfigures itself. A region where compasses lie. A cursed valley that erases trails behind you. The map might even change as you look at it.

Use this flavor sparingly. It’s potent. It’s also easy to overdo and turn into nonsense. Ground it with patterns and constraints.

Payoff: awe and dread, plus the sense that the world has rules beyond human control.

Make it playable: “tells” that signal a map is suspect

Players should have a chance to suspect, verify, and adapt. The best false maps come with subtle tells that reward attentiveness.

Try one or two of these:

- The map uses an old kingdom name no one recognizes.

- The ink is fresh, but the parchment is “ancient.”

- The compass rose points the wrong way.

- Distances are measured in a unit nobody in the region uses.

- There are suspiciously few hazards marked for such a dangerous area.

- The map’s legend doesn’t match its symbols.

- A coastline is drawn too smooth, as if guessed.

- One area is oddly blank, like it was intentionally scraped.

These aren’t “gotchas.” They’re invitations to investigate.

Verification tools: give players ways to test the map

If you want this technique to feel like clever play instead of DM sabotage, you need accessible methods for verifying information.

Common options:

- Ask locals (with social checks and the risk of misinformation).

- Compare to another map (library, guild, temple, captain, surveyor).

- Navigate by landmarks (Survival, Nature, vehicles, mounts).

- Use magical reconnaissance (familiar scouting, divination, commune).

- Follow trade routes instead of drawn lines (roads don’t lie as easily as ink).

- Use the sky (stars, sun, prevailing winds) when geography is uncertain.

The point is agency. Players should feel like they can do something about uncertainty.

The “three truths, two lies” map design trick

Here’s a simple prep method that keeps false maps from being useless.

When you create an unreliable map, decide:

- Three things the map gets right.

- Two things the map gets wrong.

Three truths make the map valuable and keep players using it. Two lies create tension and story.

Example:

- Truths: the mountain range, the old imperial road, the river crossings.

- Lies: the “safe pass,” and the location of the ruin.

Now players can still navigate, but they can’t fully trust. Perfect.

Don’t waste their time: use the breadcrumb ladder

When the party discovers the map is wrong, don’t make them start from zero. Let failure reveal the next step.

Use this three-tier breadcrumb ladder:

- Contradiction: something doesn’t match the map.

- Explanation: the party learns why it doesn’t match.

- Agency: the party gets a meaningful choice based on the truth.

Example:

- Contradiction: the “bridge” is a burned stump.

- Explanation: locals say it was destroyed in a border raid last spring.

- Agency: do you cross the river dangerously, seek a ferryman tied to smugglers, or take the long road through enemy patrols?

Now the wrong map created a decision, not a dead end.

The map itself is an NPC (treat it like one)

A good map has voice.

Ask:

- Who drew it?

- What did they want?

- What did they fear?

- What did they hide?

- Who paid for it?

Then let those answers show up as details:

- meticulous grid lines from a military surveyor,

- flourishes and saints from a monk,

- crude charcoal from a desperate fugitive,

- coded symbols from smugglers,

- overly clean borders from an imperial propagandist.

When the party reads the map, they’re meeting a character they haven’t met yet.

Counterfeit charts: how to run the con without derailing the campaign

Counterfeit treasure maps are a classic, but they’re also the easiest to mishandle. The difference between “fun scam arc” and “we wasted two sessions” is payoff pacing.

Here’s a clean structure:

Step 1: The sale

Let the party buy, steal, or receive the map. Make it enticing: a seal, a legend, a personal note, a partial sketch of a vault door. Give them a reason to bite.

Step 2: The first suspicion

Plant a small inconsistency early: a landmark name that locals don’t use, a distance that’s off, a missing bridge, or a symbol in the wrong style for the region.

Step 3: The mid-route payoff

Even if the map is fake, put something on the route: a rival party following the same chart, a bandit toll, a ruined camp of previous victims, or a hidden cache the con artist planted to keep the lie profitable.

Step 4: The reveal and the pivot

The “X” is wrong, but it points to a bigger truth: a real smuggling route, a forgotten ruin nearby, or the location of the forger’s workshop.

Step 5: The flip

Give the party a chance to turn the scam around: expose the con, steal the real ledger, force the forger to make a real map, or use the counterfeit network to bait a bigger villain.

A counterfeit map arc should end with the party feeling smarter, not mocked.

Adventure fuel: three encounters that pair beautifully with false maps

1) The fork that shouldn’t exist

The map shows one road. The terrain has two: a maintained route with patrols, and a half-swallowed path through bog and briar.

Let the choice matter. The “safe” road costs time, gold, or secrecy. The wild path costs resources, risk, or favors with the locals who know it.

2) The missing landmark

The map marks a statue at a crossroads. The crossroads exists. The statue is gone.

That absence is a clue:

- stolen as contraband,

- removed as iconoclasm,

- buried because it cursed travelers,

- moved as a signal to smugglers.

The party can solve the “where did it go?” mystery and earn information, allies, or treasure.

3) The place that appears under conditions

They reach the coordinate and find nothing. Then the ruin appears:

- only at dusk,

- only in fog,

- only during a lunar phase,

- only after a vow,

- only when no one speaks.

This is the mythic version of a false map. Keep it fair by letting players discover the rule through clues, not pure trial-and-error.

Practical mechanics: how to model unreliable maps in play

You don’t need a new subsystem, but you do need a consistent procedure. Pick one that matches your table.

Option A: Progress clock navigation

Create a clock with 6–8 segments for reaching the destination. Each day of travel, a navigator makes a check (Survival, Nature, vehicles, tools). Success marks progress. Failure marks progress but adds a complication: fatigue, lost time, an encounter, or resource loss.

The false map modifies the DC and complication list. When players verify information, reduce the DC or remove a complication.

Option B: Landmark-based travel

Instead of rolling for distance, travel becomes a chain of landmarks. The map lists them, but one or two are wrong. Each landmark is a scene: a river ford, a watchtower, a standing stone, a village.

This method makes the false map a story structure rather than a math problem.

Option C: Resource pressure

Treat bad navigation as resource loss: rations, torches, spell slots, mounts, downtime, reputation. Players can choose to spend resources to “buy certainty” (guides, better maps, bribes, divinations).

This keeps travel meaningful without bogging down in hex counts.

Using false maps to reveal lore (and make the world feel deep)

False maps are lore-delivery systems that don’t feel like exposition. When a map is wrong, the reason it’s wrong teaches the players something true.

Examples:

- Outdated map: the old empire fell, and the roads are haunted by what replaced it.

- Propaganda map: the “empty lands” are full of displaced people the regime erased.

- Counterfeit map: the merchant guild controls information and profits from ignorance.

- Myth map: the sacred route is real, but it requires ritual behavior to access.

- Reality-warp map: the region is scar tissue from an ancient spell.

The lie highlights the truth.

A ready-to-run false map mini-arc

Drop this into almost any campaign.

The party acquires a chart to the “Vault of Keryn,” stamped by the Cathedral of the Dawn. The map shows a clear route through the Hills of Brackenfold and marks the vault entrance with an X beside a waterfall.

Three truths:

- The hills are real.

- The imperial road is real (though broken).

- The waterfall is real.

Two lies:

- The vault is not behind the waterfall.

- The cathedral stamp is a forgery of an older seal.

Tells:

- The seal depicts a saint the current clergy never mention.

- The map’s script uses archaic spellings.

- The “safe campsite” is labeled with a symbol locals associate with graves.

Verification:

- A shepherd warns that the waterfall is “just water,” but the cliff above it “sings at night.”

- A retired surveyor recognizes the grid style as military, not religious.

- A local midwife knows the saint’s name from lullabies.

Payoffs:

- Following the map leads to a rival group at the waterfall, already frustrated.

- The singing cliff reveals a concealed stair when someone speaks the saint’s hymn.

- The vault is accessed by a stone arch one mile away—omitted on the map because it was scraped out.

Agency:

- Do they expose the cathedral’s historical cover-up?

- Do they keep the vault secret and profit?

- Do they return the relics to the displaced hillfolk whose history was erased?

Now the false map becomes the moral and political core of the arc, not just a detour.

Common pitfalls (and how to avoid them)

Pitfall: “Ha ha, you went the wrong way”

Fix: wrong way still yields clues, treasure, allies, or meaningful consequences.

Pitfall: The map is so wrong it’s useless

Fix: three truths, two lies. Make it partly reliable.

Pitfall: The reveal is too subtle

Fix: when the moment comes, confirm the pattern. “This portion was scraped and redrawn.” Clarity at the right time feels satisfying.

Pitfall: Players stop trusting all information

Fix: keep most sources mostly reliable. The point is discernment, not paranoia fatigue. Also reward verification so skepticism feels productive rather than cynical.

Pitfall: The technique becomes repetitive

Fix: vary the type. Use propaganda once, outdated once, myth once, counterfeit once. Different flavors, different stories.

The deeper magic: maps turn exploration into agency

Exploration in many campaigns is hard because it can feel like filler between “real scenes.” False maps fix that by making travel itself a scene with stakes and decisions.

The party is no longer just moving through the world. They are:

- evaluating sources,

- reading political pressure,

- learning history through contradictions,

- choosing who to trust,

- and deciding what truth costs.

That’s not filler. That’s play.

Advanced moves: layered maps, map economies, and “X isn’t even on the map”

Once your table has tasted one unreliable chart, you can level it up in three satisfying ways.

Layered maps are the easiest upgrade. Give the party a public, respectable map first—what merchants sell and guards use. Later, reveal a second layer: smugglers’ marks, a druidic overlay of ley lines, a pirate’s tide notes, a cult’s star-diagram, or a temple’s “thin places” between worlds. In person, you can do this with tracing paper or a second handout; in a VTT, you can toggle layers. Make the hidden layer feel earned: it’s found in a false bottom of the map tube, stitched into a satchel lining, revealed by candle heat, inked in lemon juice, or decoded with a cipher keyed to the legend.

Map economies make the world feel lived-in. If accurate maps are valuable, someone controls them. Guilds stamp official surveys. Nobles restrict border charts. Rangers sell “safe routes” with plausible deniability. Temples offer pilgrim maps that omit “sinful roads.” A simple way to model this is to treat maps like gear with quality tiers: crude sketch, local map, regional survey, military chart, secret overlay. Each tier reduces travel risk, increases speed, or reveals additional landmarks. When a counterfeit appears, it’s usually a cheap tier dressed up as a higher one, complete with fake stamps and confident claims.

Then there’s the line you want to land like a thunderclap: where X isn’t even on the map. This works best when the party learns the chart isn’t merely inaccurate—it is curated. Something has been omitted, erased, or made “unplaceable.”

Use one of these setups:

- The censored blank. The map has a suspicious pale patch where the paper looks scraped. Locals glance at it and go quiet. The missing region is a massacre site, a prison, a forbidden mine, or the “city that never was.” The party can choose to expose the truth or keep it buried.

- The shifting place. The target exists only under conditions: fog, moonlight, a vow, a debt, a song, or a season. The map isn’t wrong; it’s incomplete because the location isn’t stable. Let players discover the condition through clues and repeated motifs, not pure guessing.

- The semantic location. The destination is described by relationship rather than distance: “one day beyond the last honest confession,” “where the river forgets its name,” “beneath the bell that rings underwater.” The map cannot show it because it isn’t a coordinate until the party changes something about themselves or the world. Myth logic can be satisfying if you keep the rule consistent once it’s discovered.

One etiquette note that protects trust: when the lie is revealed, give the party a win that feels proportional. They find the real route, gain leverage over the forger, secure a guide, or earn an ally who respects their caution. The goal is not “you were fools.” The goal is “you learned how to navigate a world where information has teeth.”

Con games love this, too: a false map lets you seed mystery fast. A single handout becomes a whole plot, and verification scenes give strangers instant teamwork without needing a prologue.

Closing thought: let the world disagree with the paper

When you use unreliable maps, you’re giving your setting a pulse. Rivers change. Borders lie. Empires erase. Smugglers code. Pilgrims symbolize. Wizards warp reality. And the party is not just walking across a map—they are uncovering what the map refuses to admit.

The best moment of the False Map Technique isn’t when the players realize the chart is wrong.

It’s when they realize why it’s wrong, and that knowing the truth gives them power.

Until next time, Dear Readers...